Most climbers hire the mule service to haul their gear to base camp. At $150 per mule, I wanted to do without. I left half my food supplies with a family in Puente del Inca in order to be able to shoulder my pack. Were I to run out I expected to find expedition leftovers in base camp. Nevertheless I still had at least 80 lbs of gear and food.

Camp Berlin, located at 5850m (19,300 ft), is the highest camp on the normal route. Unfortunately, I arrived at the same time as a big storm. In the refugio I met Marcos, an Argentine climber whose partners had all given up and gone home. He helped me set up my tent where I spent the first two sleepless nights praying that it would resist the battering wind.

After seeing that dozens of tents were destroyed in the lower camp, I moved into the refugio with Marcos and two Czechs that were very difficult to communicate with. Marcos entertained by singing songs and telling stories. He also had a little radio that brought us waves of Shakira from Chile. When the storm continued the next day, the Czechs went down and left Marcos and I rubbing our feet -- depressed and quiet-- in our sleeping bags.

The next evening three Argentines climbed up to Berlin. Their enthusiasm brought hope, but nowhere near as encouraging as the ham and cheese they brought with them. Since one was a priest, we held a late night Catholic mass, my first ever, at 19,300ft. We woke at 5:00am the next morning and systematically wrapped our bodies with gear. We gave each other hugs and crawled out of the refugio to see that the infamous "Viento Blanco" was devouring the summit. Unwilling to risk the blinding winds, the Argentines abandoned the upper mountain and left Marcos and I depressed and quiet.

We spent all day shivering in our sleeping bags with our climbing clothes on. It was so cold that reading my book was out of the question. We did not even want to eat because we new it would result in pulling our pants down in the storm. We spent the days staring at the ceiling waiting for the next instant in time to come. It was so hard to consider going down because we were only a matter of hours from the top.

The next afternoon two Chileans came up and lifted our spirits again. That night the sky cleared up and the frost inside the refugio thinned out. Marcos and I did not say a word about the summit; we were bored with getting excited about a potential change in weather. But this time, the storm had passed.

Marcos had been there seven nights, and me five. You might say we were well acclimatized. We busted out of the refugio at 6:30am and did cartwheels to the summit, singing at the top of our lungs. Alright, the last 300m were very slow and very difficult. (Marcos beat me by almost an hour.) We were the first ones on top since a week prior and the weather was spectacular. Marcos went down first and I stayed on top for an hour-long siesta.

Somebody in Plaza de Mulas had told me there were only 8 km of highway that linked the Vacas Valley with Puente del Inca. Turns out there are 16 km. The unexpected 8 km challenged my strength more than the whole climb, and to make it worse, people kept offering me a ride.

I unconsciously stumbled into Puente del Inca, not realizing I had arrived until a distant voice shouted my name. It was Nano. He gave me the key to his house where I showered and fixed myself a steak and salad. Nano has a friend for life.

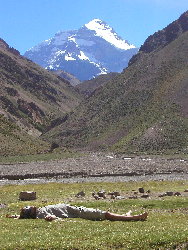

From Berlin I did the two hour traverse to the base of the Polish Glacier. I had hoped to summit again the following day via the glacier but the snow conditions were terrifying. I later learned that only four people have climbed it that season. Since I had all my gear with me, there was no need to go back to Plaza de Mulas. After seven nights above 19000 ft, I began the long descent via the Vacas Valley.